I admit my sole connection to Proust before starting Swann's Way (the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past) was this:

Whatever sense of ambling I had with The Stranger must now be stripped away as Remembrance of Things Past is the the longest novel in history with about a million and a half words in its seven volumes. Furthermore, where The Stranger was such an easy read due to Camus' hardboiled writing style,which stemmed from his lack of sentiment, Proust is sentimentality incarnate, where every emotion and every feeling is walked up and down the boulevard as if there were no word for urgency in his world.

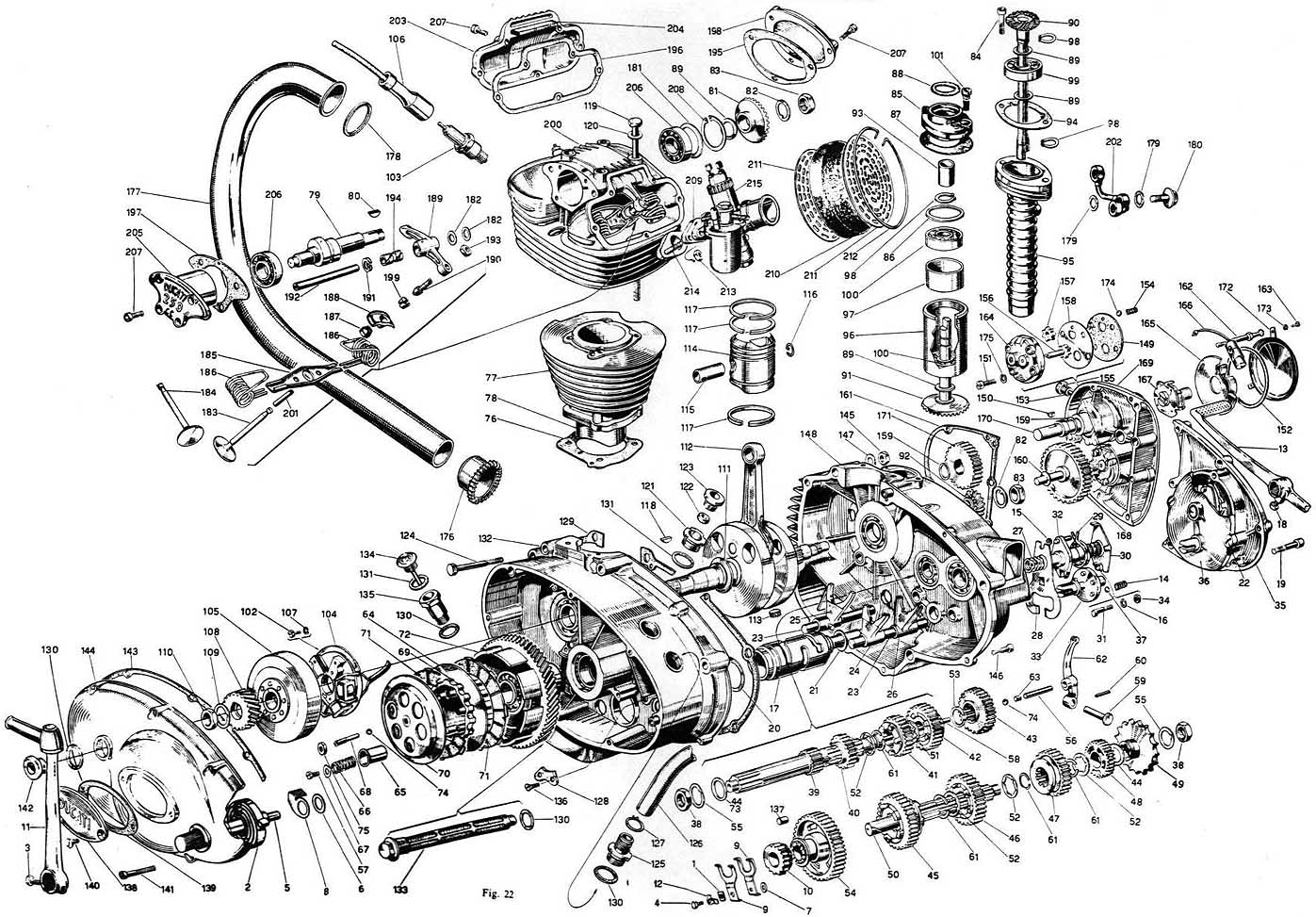

Reading Swann's Way feels like reading an auto manual where every part on a diagram is exploded and then frozen in place in order to get a full view of every piece.

Proust gives the same treatment to the formation of memories.

What is so interesting about Proust the fact that he can remain engaging even though nothing really happens in his story. He describes the brief moment of displacement that one feels upon waking that he uses as a blank canvas to inject an exploration of his entire life. In that moment, one has no context as to where one is or when one is living allowing for a brief period to be wherever or whenever a person wants to be. It's like a momentary Nirvana where only the Self exists.

The introduction of Swann has a similar effect on the Narrator's family as seen in this passage:

"And so, no doubt, from the Swann they had built up for their own purposes my family had left out, in their ignorance, a whole crowd of the details of his daily life in the world of fashion, details by means of which other people, when they met him, saw all the Graces enthroned in his face and stopping at the line of his arched nose as at a natural frontier; but they contrived also to put into a face from which its distinction had been evicted, a face vacant and roomy as an untenanted house, to plant in the depths of its unvalued eyes a lingering sense, uncertain but not unpleasing, half-memory and half-oblivion, of idle hours spent together after our weekly dinners, round the card-table or in the garden, during our companionable country life."

The man is blank enough to be whatever you want him to be.

Overture, which is the first part of Swann's Way ends on another moment where the Narrrator eats a tea-soaked Madeline - an experience that he had not had for decades, making it a pure memory (rather than a memory of another memory) and a gateway to other pure memories. Thus, setting the stage no doubt for the rest of the book.

Are you still with me? Congratulations! But, have no fear- Swann's Way, apparently, is quite self contained. So we shan't read all seven volumes.

(Unless, of course, a chorus of voices compels me.)