This is what I've been waiting for.

Not only has this book been my favorite book on Le Monde's 100 Books of the Twentieth Century, but it's possibly my new favorite book OF ALL TIME.

Boris Vian sets the stage by underpinning the entire book with a haunting song by Duke Ellington.

This song is so unique that Vian invents a dance that can only be danced to it and one other song called the "oglemee," a dance that requires dancers to undulate a certain distance away from each other at a certain tempo in order to create "a system of waves that present, as in acoustics, nodes, and antinodes, which contribute more than a little to the ambiance on a dance floor." As one advances their skill at the "oglemee," they can, in time develop the skill to produce "parasitic waves by separately putting certain of their limbs into synchronic vibration."

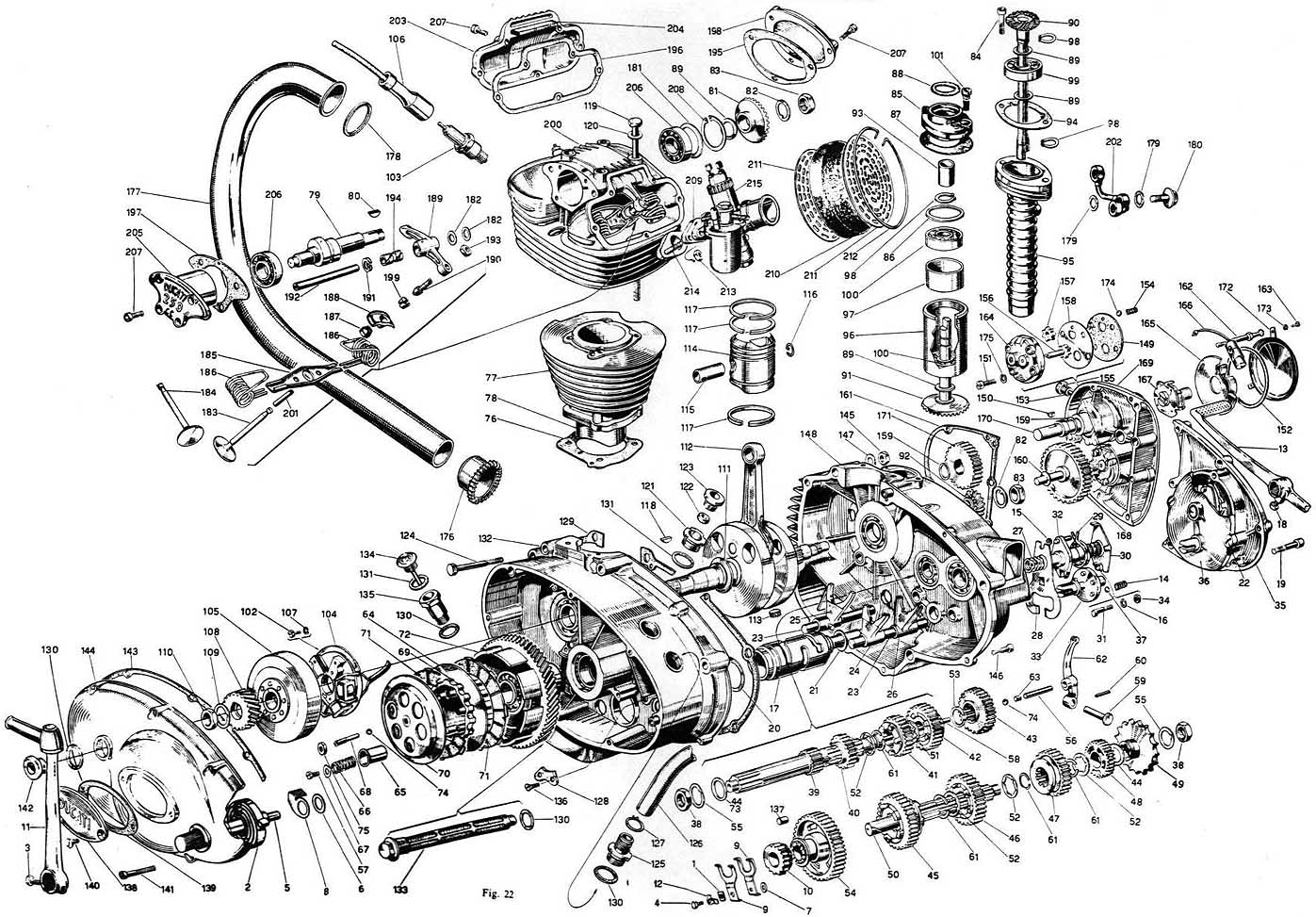

This is all very interesting but the beauty and concepts of music are taken to a more insane level with the invention of the Pianocktail.

I have no doubt that if someone built a Pianocktail in Brooklyn right now, they would dominate the cocktail scene.

Basically, a pianocktail is a piano that has different liquors, spirits, flavorings, and mixers attached to every key. Depending on the length of the note played, these drink parts are dispensed into a glass. So, every song will have a unique drink signature. Amazing!

Here is a rough sketch of a pianocktail.

Honestly, Froth on the Daydream is so good you don't want to end. It's exuberant in its anthropomorphication of everything without coming off as dopey. Plus, the cartoonish quality only amplifies the love story at the center of it.

It's the first book I've read that I've immediately wanted to re-read.

Instead, I'll just watch this pianocktail video.